A Drug Testing Trap You Need to Avoid

A drug-free workplace doesn’t just happen. It requires commitment to a safety culture by risk and safety managers, human resources professionals, supervisors, and the training department, all dedicated to knowing when and how to drug test, requirements for regulated drug tests, criteria for choosing a drug testing company, and how to counter persistent myths about drug testing. Based on emerging research, there is another aspect that may need your attention: the human factor. Failing to consider the human factor may create a drug testing trap that complicates effective substance use responses through a lack of understanding.

Who uses drugs and why?

A drug program often serves as a deterrent to drug use by formalizing the identification of employees or job candidates who use illegal drugs or abuse prescription medication. Investment in a drug program is worthwhile because drug use costs employers $740 billion annually in direct medical costs, lost productivity, absenteeism, increased health care costs, and more.1

“There is a misconception that people who use drugs fit a certain stereotype. That’s really not correct,” says Michael Berneking, MD, Concentra medical review officer and center medical director. “Many are productive members of your business and productive members of society. Three out of every four people with drug or alcohol problems are currently employed. Depending on the industry, drug testing positivity rates can be as high as 35 percent.”1 Drug use and addiction affects people from all socioeconomic groups.2

In the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, published in August 2019, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a national agency that oversees efforts to reduce substance abuse, reported that an estimated 164.8 million people were recent or current substance users, or about 60.2 percent of all Americans, age 12 and older. About 140 million drank alcohol, 60 million used tobacco products, and 32 million used illicit drugs (including 2.0 million with an opioid disorder).3

“Many people don’t understand why or how other people become addicted to drugs. They may mistakenly think that those who use drugs lack moral principles or willpower and that they could stop their drug use simply by choosing to,” said the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) in June 2018, “but drugs change the brain in ways that make quitting hard, even for those who want to.”4

“Most drugs affect the brain’s ‘reward circuit’ causing euphoria and flooding it with the chemical dopamine,” according to NIDA, “and that reward system motivates the individual to repeat behaviors that reinforce pleasurable (albeit unhealthy) activities.”

Long-term drug use can affect many of a person’s capabilities, such as these noted by NIDA:

- Learning

- Judgment

- Decision making

- Stress response

- Memory

- Behavior

Not all people who use drugs become addicted. Genetics, environment, and developmental life stages influence an individual’s response to drugs. Like alcoholism, drug addiction can be treated and managed, with medication and behavioral therapy said to offer the best chance of success.4

Deep issues can motivate drug use

Drug use, at least initially, may be about getting high or having a good time, but it may also be related to mental health issues, family or financial problems, difficulty sleeping, job dissatisfaction, or other concerns.

Companies have sought to help employees deal with persistent personal problems that can lead to drug use through the implementation of employer-sponsored, third-party employee assistance programs (EAP).

The first employer-sponsored EAPs began in the mid-to late 1930s, and coincided in both timing and purpose with the establishment of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) in 1935 by focusing on employees with alcohol problems and using the same principles as AA. After World War II, EAPs declined, only to reemerge in the 1960s and 1970s, due to not only drug and alcohol abuse, but domestic violence, depression, and other problems. Between 1971 and 1980, the number of workplace assistance programs grew from 500 to 5,000 and approximately 80 percent of Fortune 500 companies had a program available to their employees.5

Now, more than 97 percent of companies with more than 5,000 employees, 80 percent of companies with 1,001 to 5,000 employees, and 75 percent of companies with 251 to 1,000 employees provide an employee assistance program.6 Even so, only about 6.9 percent of North American employees use EAP services.7

Low utilization of EAP services generally is attributed to factors such as employees not knowing about the programs, having difficulty navigating them, or being fearful of divulging personal information. Sometimes, employees believe their problem is too small to consult a counselor because they don’t fully understand the problem’s effects.

Employers who have already established EAP services, can leverage these findings to improve current programs. Companies without existing EAP services can take this research into account to develop programs.

Drug use linked to adverse childhood experiences

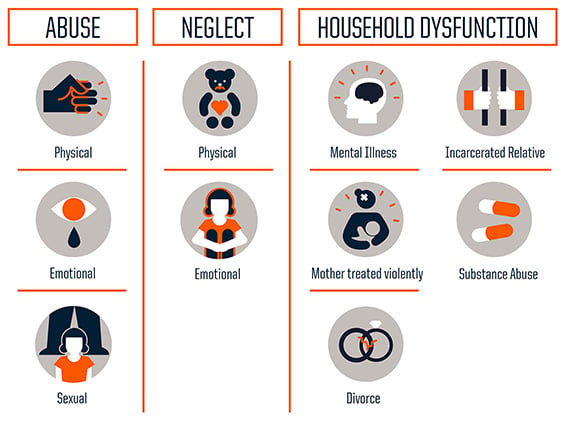

Since 1998, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has conducted more than 60 studies into what are called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), or potentially traumatic events occurring before age 18, including abuse, neglect, and household problems (absent parent, mental illness, substance abuse, and incarceration).

Source: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Source: CDC

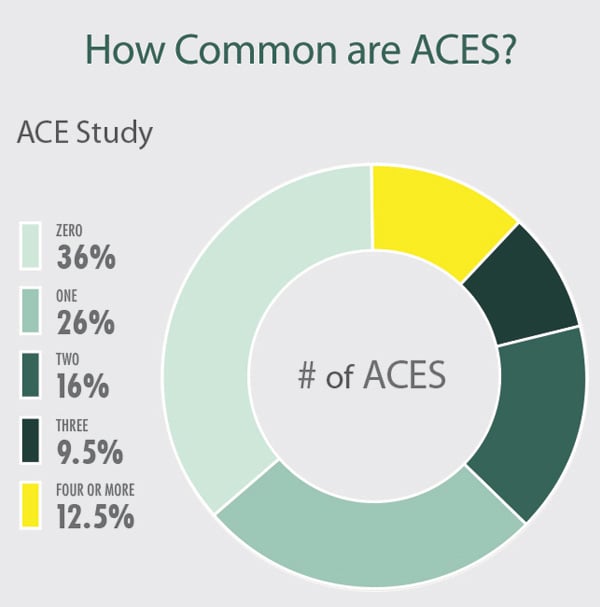

The CDC concludes that 3 in 5 adults experienced one ACE in childhood and 1 in 5 experienced four or more types of ACEs. Researchers have found a positive correlation between ACE scores and drug addiction, alcoholism, depression, suicide and chronic diseases, says Maja Jurisic, MD, CPE, Concentra vice president and medical director of strategic accounts.8

“When a score is four or greater, that’s when the risks really increase. These higher scores correlate with impaired work performance, with more absenteeism, problems performing the job, and delayed recovery when someone is injured,” explains Dr. Jurisic. The CDC estimates that 10 percent to 12.5 percent of American adults have an ACE score of four or higher.

Source: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention

Concentra® recognizes that adverse childhood experiences can be a factor in an employee turning to drugs or alcohol and also in delayed recovery from injury. “The present and the future are both affected by past experiences, so it is really helpful to understand a little bit about our patients' lives, and to approach them with curiosity and compassion,” says Dr. Jurisic.

“Having compassion for their suffering and respect for their courage and ability to survive their challenges enables our clinicians to establish a trusting therapeutic relationship,” she says.

Employers don’t need to become social workers or mental health counselors, but it is worthwhile to understand how adverse childhood experiences can foster drug addiction and other maladaptive behavior.

Law enforcement has begun using ACE research in strategies to reduce community violence. Writing in the Federal Bureau of Investigation Law Enforcement Bulletin, FBI Special Agent Christopher Freeze, MA, MS, in charge of the FBI’s office in Jackson, Mississippi, says a major challenge is embracing a new way of thinking about adults who may be acting out from vulnerable childhoods through drug addiction or violence.

“Many people mistakenly equate this quality with weakness. In reality, individuals who embody vulnerability remain open to new possibilities. Such a paradigm shift may not come easily for professionals who often see the worst in people,” Freeze says, but it offers the possibility of getting a fresh perspective, building trust, and making real change.9 In Wisconsin, Judge Mary Triggiano believes addressing ACEs early is necessary to stop a revolving door of problems, and adds, “This is about being smart about how we deal with people.”10

Research studies also have documented a link between ACEs and opioid use initiation, use, and overdose11, and between ACEs and cocaine and/or marijuana use throughout life.12, 13

Don’t confuse pre-placement and return-to-duty drug testing

Getting in touch with the human factor in drug testing also means avoiding a common mistake employers make when an employee is returning after an extended absence. You’re at high risk of making your employee angry if you order a return-to-duty test when he or she is returning from a prolonged illness, absence due to family reasons, leave of absence or military service. Why?

A return-to-duty test is required for someone who has committed a drug or alcohol violation.

Someone returning after a long illness, family concerns, military service, or leave of absence needs a pre-placement drug test.

“A return-to-duty test means the individual has committed a violation of drug or alcohol rules,” explains Dr. Berneking. “Return-to-duty testing is an observed test and will be done in the presence of a same-sex observer. An employee who did not commit a criminal violation will be very upset and confused about that.”

Follow-up testing is another type of drug test for employees with a violation, and it is done after an employee successfully passes a return-to-duty drug test. Substance abuse professionals (SAPs) oversee the return-to-work process when a drug or alcohol violation is involved, and they determine the frequency and duration of follow-up testing. “It can be up to five years; it’s at least for 12 months, but it can go on longer. It’s at the discretion of the SAP,” says Dr. Berneking.1

Conclusion

As you consider the human factor in drug testing in the context of your workforce, Dr. Berneking recommends staying current on state and local laws regarding drug testing, and to contact Concentra if we can help you navigate the requirements and create a drug program for your workplace.

NOTES

- Concentra Webinar, “What Employers Need to Know About Drug Testing,” presented by Dr. Michael Berneking, November 18, 2019.

- “Addiction Among Socioeconomic Groups,” Sunrise House.

- Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), August 2019.

- Understanding Drug Use and Addiction, National Institute on Drug Abuse, June 2018.

- Gilbert B. Employee Assistance Programs: History and Program Description. Workplace Health and Safety. 1994; 42(10): 488-493.

- Frequently Asked Questions, International Employee Assistance Professionals Association.

- Chestnut Global Partners 2016 Trends Report on Employee Assistance, Organizational Health, and Workplace Productivity.

- Concentra Webinar, “Shifting Focus from Pain to Function,” presented by Dr. Maja Jurisic, February 13, 2020.

- Christopher Freeze, MA, MS, “Adverse Childhood Experiences and Crime,” Federal Bureau of Investigation Law Enforcement Bulletin, April 9, 2019.

- Address, Wisconsin Supreme Court, November 2009.

- Stein MD, Conti MT, Kenney S, Anderson BJ, Flori JN, Risi MM, Bailey GL. Adverse childhood experience effects on opioid use initiation, injection drug use, and overdose among persons with opioid disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependency. October 2017; 179: 325-329.

- Scheidell JD, Quinn K, McGorray SP, Frueh BC, Beharie NN, Cottler LB, Khan MR. Childhood traumatic experiences and the association with marijuana and cocaine use in adolescence through adulthood. Addiction. January 2018; 113(1): 44-56.

- LeTendre ML, Reed MB. The Effect of Adverse Childhood Experience on Clinical Diagnosis of a Substance Use Disorder: Results of a Nationally Representative Study. Substance Use & Misuse. May 2017. 52(6): 689-697.